Menachem Mendel Schneerson

| Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson | |

|---|---|

| Lubavitcher Rebbe | |

Lubavitcher Rebbe |

|

| Synagogue | 770 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, NY |

| Began | 10 Shevat 5711 / January 17, 1951 |

| Predecessor | Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 5, 1902 OS (11 Nissan 5662)[1] |

| Died | June 12, 1994 NS (3 Tammuz 5754) (aged 92[2]) |

| Buried | Queens, New York, USA |

| Dynasty | Chabad Lubavitch |

| Parents | Levi Yitzchak Schneerson Chana Yanovski Schneerson |

| Spouse | Chaya Mushka Schneerson |

| Semicha | Rogatchover Gaon |

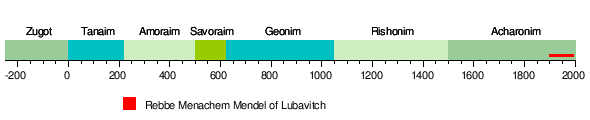

Menachem Mendel Schneerson (April 5, 1902 OS[1] – June 12, 1994 NS), known as the Lubavitcher Rebbe or just the Rebbe among his followers,[3] was a prominent Hasidic rabbi who was the seventh and last Rebbe (Hasidic leader) of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement. He was fifth in a direct paternal line to the third Chabad-Lubavitch Rebbe, Menachem Mendel Schneersohn. In January 1951, a year after the death of his father-in-law, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn, he assumed the leadership of the Lubavitch movement.

He led the movement until his death in 1994, greatly expanding its worldwide activities and founding a worldwide network of institutions to spread Orthodox Judaism among the Jewish people.[4] These institutions include schools, kindergartens, synagogues, Chabad houses, and others, and are run under the auspices of Merkos L'Inyonei Chinuch, the educational branch of the Chabad movement. His focus on messianism was controversial to some. During his lifetime many of his followers had considered him to be the Jewish Messiah, and even after his death, some continue to await his return as the Messiah.

Contents |

Early life

Birth and early years

The accepted date of his birth is 11 Nissan 5662, which is equivalent to April 5, 1902 OS or April 18, 1902 NS. (Dates in March 1895 appear on his Russian passport[5] and his application for French citizenship[6], he swore on his 1941 visa application that he "was born on the 1st day of March 1895 at Nicolaev, Kherson, Soviet Union" (now Mykolaiv, Ukraine) and was already "46 years of age" in 1941[7][8][9], and he affirmed on his U.S. draft registration card that he was 47 during World War Two and was born in "Nicolaav" on "Mar 1 1895"[10]. These statements are not considered credible evidence of his true date of birth because Jews born under the czars may have needed to claim false ages to avoid the Russian army draft.[5])

Schneerson was the eldest of three sons of Levi Yitzchak Schneerson, an authority on Kabbalah and Jewish law[11] who served as the rabbi of Yekaterinoslav from 1907 to 1939. He had two younger brothers, Dov Ber and Yisroel Aryeh Leib, both of whom were reported to be of unusual character.[12] His younger brother Dov Ber was mentally disturbed from childhood and spent his years in an institution for the mentally disabled near Nikolaiev. He died in 1944 at the hands of Nazi collaborators.[13]

The youngest, Yisrael Aryeh Leib Schneerson, was close to his brother, and often traveled with him. He was widely viewed as a genius and studied science. In the late 1920s he became a Communist, later becoming a Trotskyite. After he left the Soviet union he stopped being an observant Jew.[14] He changed his name to Mark Gourary and moved to Israel where he became a businessman, but later moved to England where he began doctoral studies at Liverpool University but died in 1951 before he completed them. His wife died in 1996 and his children—Schneerson's closest living relatives—currently reside in Israel.[12]

Early education

During his youth, Schneerson received mostly private Jewish education. He studied with Zalman Vilenkin from 1909 through 1913. In 1977, the he said of Vilenkin: “He taught me and my brothers Chumash, Rashi and Talmud. He put me on my feet. He was an illustrious Jew...”[15] When Schneerson was eleven years old, Vilenkin informed the boy's father that he had nothing more to teach his son.[16]

Schneerson later studied independently under his father, who was his primary teacher. He studied Talmud and rabbinic literature, as well as the Hasidic view of Kabbalah. He received his rabbinical ordination from the Rogatchover Gaon, Yosef Rosen,[17] and from Rabbi Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg (also known as the Sridei Aish).[18]

Schneerson's mother said her son never attended any Soviet school, though he took the exams as an external student and did well on them[19] According to Avrum Ehrlich, he immersed himself in Jewish studies while simultaneously qualifying for Russian secondary school.[12] Throughout his childhood Schneerson was involved in the affairs of his father's office, where his secular education and knowledge of the Russian language were useful in assisting his father's public administrative work. He was also said to have acted as an interpreter between the Jewish community and the Russian authorities on a number of occasions.[12]

Early travels and marriage

In 1923 Schneerson visited Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn for the first time. It was presumably at that time that he met Schneersohn's middle daughter, Chaya Mushka.[12] He became engaged to her in Riga in 1923 and married her five years later in 1928, after being away in Berlin. He returned to Warsaw for his wedding, and in an article about his wedding in a Warsaw newspaper, "a number of academic degrees" were attributed to him. Following the marriage, the newlyweds went to live in Berlin. The marriage was long and happy (60 years), but childless.

Schneerson and Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn are related through Tzemach Tzedek, the third Rebbe of Chabad Lubavitch.

Berlin

Studies

Schneerson studied mathematics, physics and philosophy in Berlin, Germany for five semesters from mid-1928 through 1930.[20] Professor Menachem Friedman found his records amongst the students who "audited courses at the university without receiving academic credit." While he was there, he composed hundreds of pages of original Torah discourses, subsequently published as "Reshimot,[21]" and corresponded with his father on Torah matters, which were published in the 1970s in the book "Likuttei Levi Yitzchak—Letters.[22]"

With his brother

His brother, Yisroel Aryeh Leib (known to Lubavitchers as 'Leibel' and to others by his secular name, 'Liova'), joined him in Berlin in 1931, traveling with false papers under the name 'Mark Gurary' to escape the Soviets. He arrived and was cared for by his brother and sister-in-law as he was seriously ill with typhoid fever. Leibel attended classes at the University of Berlin from 1931 to 1933. In 1933, after Hitler took over Germany and began instituting anti-Semitic policies, Mendel and his wife helped Leibel escape from Berlin, before themselves fleeing to Paris.[20] Leibel escaped to Mandate Palestine in 1939 with his fiancee Regina Milgram, where they later married.[23] Despite Leibel's secularism, the two brothers maintained a relationship.[12]

Encounters with Rabbi J. B. Soloveitchik

Some students of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, have asserted that Schneerson met Soloveitchik while they were studying in Berlin.[24][25][26]

Soloveitchik's daughter Dr. Atarah Twersky recalls Soloveitchik saying that Schneerson visited her father in his apartment and the former asked the latter why he was studying in Berlin if his father-in-law was opposed to it. Other sources deny this. According to Soloveitchik's son Rabbi Dr. Haym Soloveitchik, Rabbi Soloveitchik only saw Schneerson pass by in Berlin and they did not meet while there.[27]

France

In 1933, Schneerson moved to Paris, France. He studied mechanics and electrical engineering at the École spéciale des travaux publics, du bâtiment et de l'industrie (ESTP), a Grandes écoles in the Montparnasse district. He graduated in July 1937 and received a license to practice as an electrical engineer. In November 1937, he enrolled at the Sorbonne, where he studied mathematics until World War II broke out in 1939.[28] Schneerson lived most of the time in Paris at 9 Rue Boulard in the 14th arrondissement, in the same building as his wife's sister, Shaina, and her husband, Mendel Hornstein, who was also studying at ESTP. Mendel Hornstein failed the final exams and he and his wife returned to Poland; they were murdered at Treblinka in late 1942. On June 11, 1940, three days before Paris fell to the Nazis, the Schneersons fled to Vichy, and later to Nice, where they stayed until their final escape from Europe.[29]

Schneerson learned to speak French, which he put to use in establishing his movement there after the war. The Chabad movement in France was later to attract many Jewish immigrants from Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia.

America and leadership

Escape from Europe

In 1941, Schneerson escaped from Europe on the Serpa Pinto, which embarked from Lisbon, Portugal. It was one of the last boats to cross the Atlantic before the U-boat blockade began,[30] and joined his father-in-law, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn, in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn, New York. Seeking to contribute to the war effort, he went to work in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, drawing wiring for the battleship USS Missouri (BB-63),[31][32] and other classified military work.[33]

Rise in America

In 1942, his father-in-law appointed him director of the Chabad movement's newly-founded central organizations, placing him at the helm of building the movement's Jewish educational, social services, and publishing networks across the United States, Israel, Africa, Europe and Australia. However, Schneerson kept a low public profile within the movement. He would speak publicly only once a month, delivering talks to his father-in-law's followers.[12]

During the 1940s, Schneerson became a naturalized US citizen. For many years to come, he would speak about America's special place in the world, and would argue that the bedrock of the United States' power and uniqueness came from its foundational values, which were, according to Schneerson, '"E pluribus unum'—from many one", and "In God we trust."[34] In 1949, his father-in-law would become a U.S. citizen, with the Rebbe assisting to coordinate the event. A special dispensation was arranged wherein the federal judge came to "770" to officiate at Rabbi Yoseph Yitzchak's citizenship proceedings, rather than the wheelchair-bound Rebbe travel to a courthouse for the proceedings. Uniquely, the event was recorded on color motion film.[35]

Candidate for Rebbe

Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn died in 1950. The two main candidates for leadership were Schneerson and Rabbi Shemaryahu Gurary, Schneersohn's elder son-in-law. Schneerson actively refused to accept leadership of the movement for the entire year after Schneersohn's passing but was eventually cajoled into accepting the post by his wife and followers.[36] On the first anniversary of his father-in-law's passing, 10 Shevat 1951, he delivered a Hasidic discourse, (Ma'amar), and formally became the Rebbe.[37]

Activities as Rebbe

Jewish outreach

Schneerson believed that the American public was seeking to learn more about their Jewish heritage. He stated, "America is not lost, you are not different. You Americans sincerely crave to know, to learn. Americans are inquisitive. It is Chabad's point of view that the American mind is simple, honest, direct—good, tillable soil for Hassidism, or just plain Judaism".[38] Schneerson believed that Jews need not be on the defensive, but need to be on the ground building Jewish institutions, day schools and synagogues. Schneerson said that we need "to discharge ourselves of our duty and we must take the initiative".[39]

Schneerson placed a tremendous emphasis on outreach. He made great efforts to intensify this program of the Chabad movement, bringing Jews from all walks of life to adopt Torah-observant Judaism, and aggressively sought the expansion of the baal teshuva movement. His work included organizing the training of thousands of young Chabad rabbis and their wives, who were sent all over the world by him as shluchim (emissaries) to spread the Chabad message.

He oversaw the building of schools, community centers, youth camps, and "Chabad Houses", and established contacts with wealthy Jews and government officials around the world. Schneerson also instituted a system of "Chabad mitzvah campaigns" called mivtzoim to encourage Jews to follow Orthodox Jewish practices. They commonly centered on practices such as keeping kosher, lighting Shabbat candles, studying Torah, putting on tefillin, helping to write sifrei Torah, and teaching women to observe the laws of Jewish family purity. He also launched a global Noahide campaign [1] to promote observance of the Noahide Laws[40] among gentiles, and argued that involvement in this campaign is an obligation for every Jew.[41]

Political activities

Israel

Schneerson never visited the State of Israel, where he had many admirers. However, many among Israel's top leadership made it a point to visit him and they were grandly received. One of Israel's presidents, Zalman Shazar, who was of Lubavitch ancestry, would visit Schneerson and corresponded extensively with him. Menachem Begin, Ariel Sharon, Moshe Katzav, and later, Benjamin Netanyahu - who was present at his funeral -, also paid visits and sought advice, along with numerous other less famous politicians, diplomats, military officials, and media producers. In the elections that brought Yitzhak Shamir to power, Schneerson publicly lobbied his followers and the Orthodox members in the Knesset to vote against the Labor alignment. It attracted the media's attention and led to articles in Time, Newsweek, and many newspapers and TV programs, and led to considerable controversy within Israeli politics.

He lobbied Israeli politicians to pass legislation in accordance with Jewish religious law on the question "Who is a Jew?" and declare that "only one who is born of a Jewish mother or converted according to Halakha is Jewish." This caused a furor in the United States. Some American Jewish philanthropies stopped financially supporting Chabad-Lubavitch since most of their members were connected to Reform and Conservative Judaism. These unpopular ideas were toned down by his aides, according to Avrum Erlich. "The issue was eventually quietened so as to protect Chabad fund-raising interests. Controversial issues such as territorial compromise in Israel that might have estranged benefactors from giving much-needed funds to Chabad, were often moderated, particularly by...Krinsky."[42] Rabbi Immanuel Jakobovits argued that Chabad moderated its presentation of anti-Zionist ideology and right-wing politics in England and downplayed its messianic fervor so as not to antagonize large parts of the English Jewish community.[42]

Iran

Beginning in the Winter of 1979, during the tumultuous days of the Islamic Revolution in Iran, Schneerson directed his emissaries to make arrangements to rescue Jewish teenagers from Iran and place them in foster homes within the Lubavitcher community in Brooklyn. This mission, while not political in nature, was originally started as a secretive quest in order not to jeopardize the safety of the Iranian Jewish Community at large. Many of Schneerson followers in Brooklyn were asked to open their homes to these Jewish children and help save their lives from another potential Holocaust in the making. The new Islamic government in Iran was vocally opposed to the existence of Israel and created a genuine concern in world Jewish circles by accusing many in the Jewish community of being Zionists. The execution of the leader of the Iranian Jewish community , Habib Elghanian had made this a tangible threat to the very existence of the community. Ultimately, while more than a dozen members of the Jewish community were executed by the new Iranian government, Jews were allowed to continue to live in Iran and there would be no Holocaust. Hundreds of Jewish children from Tehran and other major cities in Iran were flown from Tehran to New York with the help of Schneerson's emissaries, placed in foster homes in Crown Heights and educated in Chabad schools. Many would adopt the Lubavitcher lifestyle and later, some even served as Chabad emissaries and religious leaders. Many others would later reunite with their biological parents after their parents and other family members emigrated to the United States.

Scholarship

Rabbi Schneerson is known for his scholarship both in the Talmud and hidden parts of the Torah (both Kabbalah and Chasidus). He is especially renowned for his insights on, and analysis of Rashi's Torah commentary. In halachic matters, he normally deferred to members of the Crown Heights Beth Din headed by Rabbi Zalman Shimon Dvorkin, and advised the movement to do likewise in the event of his death.[43] While Schneerson rarely chose to involve himself with questions of halakha (Jewish law), some notable exceptions were with regard to the use of electrical appliances on Shabbat, sailing on Israeli boats staffed by Jews, and halakhic dilemmas related to certain religious observances which may arise when crossing the International Date Line.

Public addresses

Schneerson was known for delivering regular lengthy addresses to his followers at public gatherings, with only brief notes outlining the points he planned to discuss. These talks usually centered on the weekly Torah portion, and were then transcribed by followers known as choizerim, and distributed widely. Many of them were later edited by him and distributed worldwide in small booklets, later to be compiled in the Likkutei Sichot set. He also penned tens of thousands of replies to requests and questions. The majority of his correspondence is printed in Igrot Kodesh, partly translated as "Letters from the Rebbe". His correspondence fills more than two hundred published volumes.[31]

"770"

Schneerson rarely left Crown Heights in Brooklyn except for frequent lengthy visits to his father-in-law's gravesite in Queens, New York. A year after the passing of his wife, Chaya Mushka, in 1988, when the traditional year of Jewish mourning had passed, he moved into his study above the central Lubavitch synagogue at 770 Eastern Parkway.

It was from this location that Schneerson directed his emissaries' work and involved himself in details of his movement's developments. His public roles included celebrations called farbrengens (gatherings) on Shabbats, Jewish holy days, and special days on the Chabad calendar, when he would give lengthy sermons to crowds. In later years, these would often be broadcast on cable television and via satellite to Lubavitch branches around the world.

Later life

Illness

In 1977, Schneerson suffered a massive heart attack while celebrating the hakafot ceremony on Shemini Atzeret. Despite the best efforts of his doctors to convince him to change his mind, he refused to be hospitalized.[44] This necessitated building a mini-hospital in his headquarters at "770." Although he did not appear again in public for many weeks, Schneerson continued to deliver talks and discourses from his study via intercom. His chief cardiologist Dr. Ira Weiss later stated that despite his own protestations against the Rebbe's being treated in 770, in retrospect, it had turned out to be the correct decision, and "the Rebbe, in fact received better medical care in 770 than he would have had we taken him to the hospital."[45] On Rosh Chodesh Kislev, he left his study for the first time in more than a month to go home. His followers celebrate this day as a holiday each year.

Honors

On March 25, 1983, on the occasion of his 80th birthday, the United States Congress proclaimed Rabbi Schneerson's birthday as "Education Day, USA," and awarded him the National Scroll of Honor.[46]

"Sunday Dollars"

As the Chabad movement grew and more demands were placed on Schneerson's time, he limited his practice of meeting followers individually in his office. After his heart attack in 1977, he stopped his twice-weekly practice of Yechidut—private audiences with whomever would request an appointment—although community leaders and Israeli government officials would still occasionally meet with the Rebbe in private.

In 1986, Schneerson again began to regularly greet people individually. This time, the personal meetings took the form of a weekly receiving line in "770". Almost every Sunday, thousands of people would line up to meet briefly with Schneerson and receive a one-dollar bill, which was to be donated to charity. People filing past Schneerson would often take this opportunity to ask him for advice or to request a blessing. This event is usually referred to as "Sunday Dollars."[47] Beginning in 1989, the events were recorded on videotape. Posthumously, hundreds of thousands these encounters were posted online[48] for public access.

Death of his wife

Following the death of his wife in 1988, Schneerson withdrew from some public functions. For example, he stopped delivering addresses during weekdays, instead holding gatherings every Shabbat.[49] He later edited these addresses, which have since been released in the Sefer HaSichos set.

According to Ehrlich, towards the end of his life, particularly after his heart attack in 1977, Schneerson's scholarship began to fade. He writes that one of Schneerson's editors, David Olidort, "told how most of Schneerson’s aides and editors adored him and saw him as virtually infallible, despite their numerous corrections of his failing scholarship."[50]

Final years

"Moshiach" (Messiah) fervor

Some of Schneerson's followers believed he was the Jewish Messiah, the "Moshiach," and have persisted in that belief since his death. The reverence with which he was treated by followers led many Jewish critics from both the Orthodox and Reform communities to allege that a cult of personality had grown up around him.[51] Moshe D. Sherman, an associate professor at Touro College wrote that "as Schneerson's empire grew, a personality cult developed around him... portraits of Schneerson were placed in all Lubavitch homes, shops, and synagogues, and devoted followers routinely requested a blessing from him prior to their marriage, following an illness, or at other times of need."[52]

His own stated goals

From his childhood and throughout the years of his leadership, the Rebbe explained that his goal was to "make the world a better place,[53]" and to eliminate suffering. In 1954, in a letter to Yitzchak Ben Tzvi, Israel's second President, the Rebbe wrote: "From the time that I was a child attending cheder, and even before, the vision of the future Redemption began to take form in my imagination – the Redemption of the Jewish People from their final Exile, a redemption of such magnitude and grandeur through which the purpose of the suffering, the harsh decrees and annihilation of Exile will be understood...[54]"

Final declarations

In 1991, he declared to his followers: "I have done everything I can [to bring Moshiach], now I am handing over to you [the mission]; do everything you can to bring Moshiach!" A campaign was then started to usher in the Messianic age through "acts of goodness and kindness," and some of his followers placed advertisements in the mass media, including many full-page ads in the New York Times, declaring in Rabbi Schneerson's name that the Moshiach's arrival was imminent, and urging everyone to prepare for and hasten it by increasing their good deeds.

Crown Heights riot

In 1991, Schneerson was indirectly involved in the start of a riot in his neighborhood of Crown Heights. The riot began when a car accompanying his motorcade—returning from one of his regular cemetery visits to his father-in-law's grave—accidentally struck two seven-year-old African American children, killing one boy. In the rioting, Australian-born Jewish graduate student Yankel Rosenbaum was murdered, many Lubavitchers were badly beaten, and much property was destroyed; also, rioters hurled rocks and bottles at the Jews over police lines.[55]

Final illness

In 1992, Schneerson suffered a serious stroke while praying at the grave of his father-in-law. The stroke left him unable to speak and paralyzed on the right side of his body. Nonetheless, he continued to respond daily to thousands of queries and requests for blessings from around the world. His secretaries would read the letters to him and he would indicate his response with head and hand motions. During this time, the belief in Schneerson as the Messiah became more widespread.[56]

Despite his deteriorating health, Schneerson once again refused to leave "770". Several months into his illness, a small room with tinted glass windows and an attached balcony was built overlooking the main synagogue. This allowed Schneerson to pray with his followers, beginning with the Rosh Hashanah services, and to appear before them after services either by having the window opened or by being carried out onto the balcony.

His final illness led to a split between two groups of aides who differed in their recommendations as to how Schneerson should be treated, with the two camps led by Leib Groner and Yehuda Krinsky.[57][58]

Aides argued over whether Schneerson had the same physical makeup as other humans, and if the illness should be allowed to run its course without interference. Krinsky argued that the latest and most suitable medical treatment available should be used in treating Schneerson, while Groner thought that "outside interference in the Rebbe’s medical situation might be just as dangerous as inaction. They saw his illness as an element in the messianic revelation; interference with Schneerson’s physical state might therefore affect the redemptive process, which should instead be permitted to run its natural course."[58]

Death and burial

Schneerson died at the Beth Israel Medical Center on June 12, 1994 (3 Tammuz 5754) and was buried at the Ohel next to his teacher and father-in-law, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, at Montefiore Cemetery in Queens, New York,[59] in 1994.[60][61] The Ohel had been built around the Previous Rebbe's grave in 1950.

Ohel Chabad-Lubavitch Center

Soon after Schneerson's passing, philanthropist Joseph Gutnick of Melbourne, Australia established the Ohel Chabad-Lubavitch Center on Francis Lewis Boulevard, Queens, New York, which is located adjacent to the Rebbe's Ohel. Following the age-old Jewish tradition of turning the resting place of a tzadik into a place of prayer, thousands of people flock to the Rebbe's resting place every week.[62] Many more send faxes and e-mails with requests for prayers to be read at the grave site.

U.S. Government awards

Starting with President Carter in 1978,[63] the U.S. Congress and President have issued proclamations each year, declaring that Schneerson's birthday — usually a day in March or April that coincides with his recognized Hebrew calendar birthdate of 11 Nissan — be observed as Education and Sharing Day in the United States.[64] The Rebbe would usually respond with a public address [65] on the importance of education in modern society, and holding forth on the United States' special role in the world.

Honored by Congress

After Schneerson's death, a bill was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives—sponsored by Congressman Charles Schumer and cosponsored by John Lewis, Newt Gingrich, and Jerry Lewis, as well as 220 other Congressmen—to posthumously bestow upon Schneerson the Congressional Gold Medal.

On November 2, 1994 the bill passed both Houses by unanimous consent, honoring Schneerson for his "outstanding and enduring contributions toward world education, morality, and acts of charity".[66] President Bill Clinton spoke these words at the Congressional Gold Medal ceremony:

| “ | The late Rebbe's eminence as a moral leader for our country was recognized by every president since Richard Nixon. For over two decades, the Rabbi's movement now has some 2000 institutions; educational, social, medical, all across the globe. We (the United States Government) recognize the profound role that Rabbi Schneerson had in the expansion of those institutions. | ” |

Other posthumous commendations

In 2009, the National Museum of American Jewish History[67] selected Schneerson as one of eighteen Jewish Americans to be included in their "Only in America" Hall of Fame.

Controversy

Wills

There is considerable controversy within Chabad about Schneerson's will. It is widely accepted that two wills exist, the first will was signed by Schneerson and transferred stewardship of all the major Chabad institutions to Rabbi Yehuda Krinsky.[68] This will is indisputable as it was officially filed and a record of its signing exists in the archives of New York State.

The second will gave the bulk of control to three senior Chabad rabbis, Rabbis Mindel, Pikarski and Hodakov (contemporary of Schneerson) and gave Krinsky only a minor role. The only copy of this will, that was drafted by others, is unsigned. Supporters of Krinsky argue that the will was merely presented to Schneerson, who chose not to sign it.[68] Supporters of the messianist camp, led by Leib Groner argue that the will was signed but that interested parties destroyed or hid the signed copy to gain power.[68]

The first will, signed and dated February 14, 1988, transferred power over all Schneerson’s property and personal effects to Agudas Chasidei Chabad (AGUCH) (directed by Krinsky), naming Krinsky as sole executor.[68] Avrum Erlich, a Chabad chronicler and scholar summarises the dispute:

| “ | After the [second] will was prepared, Schneerson said he would look it over before signing it, and that is apparently the last that was seen of it. Some Habad members believe that Schneerson never signed this will... others believe that even if the will was not signed, it is nevertheless indicative of his general view. There are still others who believe that a signed copy of the will exists, but was stolen from Schneerson’s drawer and hidden by an interested party who hopes to gain by its destruction.[68] | ” |

Krinsky was called to testify before the Chabad Beit Din on the authenticity or otherwise of the disputed second will, but he refused to do so, contending that a local Crown Heights rabbinic body had no authority over international Lubavitch institutions.[68] Krinsky's stewardship of the movement has been a bone of contention amongst Chabad followers and emissaries who see him as trying to control the movement by subsuming it under the umbrella of the AGUCH.[68]

Schneerson as the Jewish Messiah

Before Schneerson's death in 1994 many Chabad Hasidim believed that he was soon to become manifest as the Messiah — an event that would herald the Messianic Age and the construction of the Third Temple. Books and pamphlets were written arguing that the Rabbi was the Messiah.

In Schneerson's later years a movement arose believing that it was their mission to convince the world of his messiahship, and that general acceptance of this claim would lead to his revelation. Adherents to this belief were termed Meshichist. In the early '90s, his followers sang the song "Yechi Adoneinu Moreinu v'Rabbeinu Melech haMoshiach l'olom vo'ed!" (English: "[Long] Live our Master, our Teacher, and our Rabbi, King Messiah, for ever and ever!"), and Schneerson encouraged them with hand motions.[69] After his stroke the singing and the encouragement became routine.

A spectrum of beliefs exists today within the Chabad movement regarding Schneerson and his purported position as the Messiah.[70] While some believe that he died but will return as the Messiah, others believe that he is merely "hidden." Other groups believe that he has God-like powers, while a few negate the idea that he is the messiah entirely. The prevalence of these views within the movement is disputed,[71][72][73] though very few will openly say that Schneerson cannot be the Messiah.[71]

Beginnings

The belief that Schneerson is the Messiah can be traced to the 1950s; it picked up momentum during the decade preceding Schneerson's death in 1994,[74] and has continued to develop since his death.[75] The response of the wider Haredi and Modern Orthodox communities to this belief has been antagonistic; the issue remains controversial within the Jewish world.[76][77][78][79]

Among his followers

His followers continue to visit his resting place at the Ohel, believing, in the words of the Tanya—the seminal work of Chabad Hasidism—that "The righteous, in their passing, can bless those in this world more so than during their lifetimes.[80]"

However, a minority of his followers take this belief a step further, contending that he is able to answer their questions from beyond the grave, through a process of bibliomancy using his collected letters. This practice is known as "Igrot Kodesh", by which answers to questions are derived through consulting the published collections of Schneerson’s letters known as the Igrot Kodesh.[81][82]

References

- Hoffman, Edward (1991). Despite all odds: the story of Lubavitch. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0671677039. OCLC 22113189. LCCN 90-10115.

- Ehrlich, Avrum M. (2004). The Messiah of Brooklyn: understanding Lubavitch Hasidism past and present. Jersey City, New Jersey: KTAV Publishing. ISBN 0881258369. OCLC 55800922. LCCN 2004-14552.

- ^ a b The accepted date is April 5, 1902 OS. However, government documents, including his Russian passport, his application for French citizenship, his application for a U.S. visa, and his U.S. World War Two draft registration all indicate he was born in March 1895.

- ^ 92 based on accepted date of birth in 1902; 99 based on the 1895 date that appears on government documents

- ^ Encyclopedia Judaica, Second Edition, Volume 18 page 149

- ^ "National Geographic Magazine February 2006". Ngm.nationalgeographic.com. http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/0602/feature4/index.html. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ^ a b The Rebbe: The Life and Afterlife of Menachem Mendel Schneerson. Princeton University Press. 2010. p. 66. http://books.google.com/books?id=QuWQ3DiYGVwC&pg=PA66&lpg=PA66&dq=schneerson+birth+1895&source=bl&ots=XAFGeBEAU-&sig=VteQGs3nS1lXqlFH_95_DxtxhCk&hl=en&ei=4qgSToWMLpGasAOysICuDg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CCYQ6AEwAQ#. Retrieved 2011-07-04.

- ^ "NATURALISATION M. SCHNEERSON" (in French). http://soc.qc.cuny.edu/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/Schneerson-France-Naturalization-file.pdf. Retrieved 2011-07-06.

- ^ Runyan, Joshua. "News: Team Unearths Rebbe’s 1941 U.S. Visa Application". Chabad.org. http://www.chabad.org/therebbe/article_cdo/aid/1559223/jewish/Research-Team-Unearths-Rebbes-1941-US-Visa-Application.htm. Retrieved 2011-07-04.

- ^ "APPLICATION FOR IMMIGRATION VISA (QUOTA)". http://www.chabad.org/multimedia/browsers/imagepopup_cdo/iid/5443084. Retrieved 2011-07-04.

- ^ "APPLICATION FOR IMMIGRATION VISA (QUOTA)". http://www.chabad.org/multimedia/browsers/imagepopup_cdo/iid/5443091. Retrieved 2011-07-04.

- ^ "REGISTRATION CARD--(Men born ... on or before February 16, 1897". http://soc.qc.cuny.edu/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/Mendel-draft-card.jpg. Retrieved 2011-07-06.

- ^ Introduction to Likkutei Levi Yitzchak, Kehot Publications 1970

- ^ a b c d e f g Ehrlich 2004, Chapter 4

- ^ Larger Than Life, Deutsch, S. S., vol. 2, pp. 125–145.

- ^ Larger Than Life, Deutsch, S. S., vol. 1, pp. 101–103, and vol. 2, p. 118

- ^ Sichos Kodesh 5738, Volume 1, page 596

- ^ Chana Vilenkin, Zalman's daughter on "The Early Years Vol I". Jewish Educational Media 2006, segment Nikolaev, Russia 1902. (UPC 874780 000525)

- ^ Selegson, Michoel A. Introduction to From Day to Day, English translation of the Hayom Yom (ISBN 08266-06695), p. A20.

- ^ http://www.chabad.org/therebbe/livingtorah/player_cdo/aid/1264762/jewish/Rabbinic-Ordination.htm.

- ^ Schneerson, Chana, A Mother in Israel Kehot Publications 1983 (ISBN 08266-00999)page 13.

- ^ a b "The Early Years Volume II (1931–1938)" Jewish Educational Media, 2006 (UPC 74780 00058)

- ^ Reshimot, 5 Volumes, Kehot Publication Society, 1994–2003

- ^ Likkutei Levi Yitzchak Igrot Kodesh, Kehot Publication Society, 1972

- ^ (ISBN 0-9647243-0-8) Vol. II, p.134)

- ^ Kowalsky, Sholem B.. "The Rebbe and the Rav". Chabad.org. http://www.chabad.org/therebbe/article.htm/aid/529444/jewish/The-Rebbe-and-the-Rav.html. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- ^ (Windows Media Video) A Relationship from Berlin to New York (Documentary). Brooklyn, NY: Chabad.org. http://www.chabad.org/therebbe/article.htm/aid/527750/jewish/A-Relationship-from-Berlin-to-New-York.html. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- ^ (Windows Media Video) The Rebbe in Berlin, Germany (Documentary). Brooklyn, NY: Chabad.org. http://www.chabad.org/therebbe/article.htm/aid/527752/jewish/The-Rebbe-in-Berlin-Germany.html. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- ^ "Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik and Abraham Joshua Heschel on Jewish-Christian Relations" by Rabbi Reuven Kimelman

- ^ "The Early Years Volume III (1938–1940)", Jewish Educational Media, 2007

- ^ The Early Years Volume IV, JEM 2008 (ASIN: B001M1Z62I)

- ^ Last Sea Route From Lisbon to U.S. Stops Ticket Sale to Refugees, New York Times, March 15, 1941

- ^ a b Fishkoff, Sue. The Rebbe's Army, Schoken, 2003 (08052 11381). Page 73. Milton Fechtor, Wiring the Missouri, Jewish Educational Media.

- ^ Living Torah Vol 53 Episode 210, "Rabbi Engineer, Part 1: The Brooklyn Navy Yard", Jewish Educational Media

- ^ No One There, but This Place Is Far From Empty NY Times January 14, 2009 By ALAN FEUER

- ^ Address, January 15, 1981 http://www.chabad.org/1180692/

- ^ http://www.chabad.org/471239/

- ^ Leadership in the HaBaD Movement, Avrum M. Ehrlich, Jason Aronson, January 6, 2000, ISBN 076576055X

- ^ "Shevat 10: A Day of Two Rebbes". Chabad.org. http://www.chabad.org/library/article.asp?AID=108303. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ^ Raddock, Charles, The Jewish Forum, April, 1951

- ^ Kranzler, Gershon, Jewish Life, Sept.–Oct. 1951.

- ^ "Universal Morality - Action". Chabad.org. http://www.chabad.org/therebbe/article_cdo/aid/62221/jewish/Universal-Morality.htm. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ^ "Essays: Educating Mankind". Sichosinenglish.org. http://www.sichosinenglish.org/essays/01.htm. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ^ a b Ehrlich 2004, Chapter 14 notes

- ^ The Messiah of Brooklyn: Understanding Lubavitch Hasidim Past and Present, M. Avrum Ehrlich, Chapter 15, (also see note 10 Ibid.) KTAV Publishing, ISBN 0881258369

- ^ Hoffman 1991, p. 46

- ^ Testimony by Dr. Weiss on Living Torah, Jewish Educational Media, disc 42, program 166; Disc 56, program 223; and disc 67, program 267—viewable at http://www.chabad.org/therebbe/livingtorah/default.asp?searchword=weiss&LocalSearchImg.x=0&LocalSearchImg.y=0

- ^ http://www.chabad.org/therebbe/article_cdo/aid/142535/jewish/The-Rebbe-and-President-Reagan.htm

- ^ Hoffman 1991, p. 47

- ^ mymomentwiththerebbe.com

- ^ Lipkin, p. 79

- ^ The Messiah of Brooklyn: Understanding Lubavitch Hasidim Past and Present, M. Avrum Ehrlich, Chapter 8, p. 80, note 35. KTAV Publishing, ISBN 0881258369

- ^ Rabbi Schneerson Led a Small Hasidic Sect to World Prominence New York Times Obit, Aril Goldman, June 13, 1994

- ^ Orthodox Judaism in America: A Biographical Dictionary and Sourcebook, pg. 187 Moshe D. Sherman, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1996

- ^ Schneerson, Rabbi Menachem Mendel, Sefer Hama’amorim Melukot Al Seder Chodshei Hashana Volume 2 Kehot Publications 2002 (ISBN 978-1-562-602-9) page 271.

- ^ Schneerson, Rabbi Menachem Mendel, Igros Kodesh Volume 12 Kehot Publications 1989 (ISBN 0-8266-5812-12) page 404.

- ^ Hasid Dies in Stabbing; Black Protests Flare 2d Night in a Row By JOHN KIFNER New York Times (1857-Current file); August 21, 1991; ProQuest Historical Newspapers The New York Times (1851–2003)pg. B1

- ^ The Washington Post, June 20, 1999. 5 Years After Death, Messiah Question Divides Lubavitchers. Leyden, Liz.

- ^ Gonzalez, David (1994-11-08). "''Lubavitchers Learn to Sustain Themselves Without the Rebbe'', David Gonselez, New York Times, November 8, 1994". New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C01E0D6133EF93BA35752C1A962958260. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ^ a b The Messiah of Brooklyn: Understanding Lubavitch Hasidim Past and Present, M. Avrum Ehrlich, Chapter 14, KTAV Publishing, ISBN 0881258369

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Hasidism, by Tzvi Rabinowicz p. 432 ISBN 1568211236.

- ^ The New York Times, June 13, 1994, p. A1.

- ^ Menachem Mendel "The Rebbe" Schneerson at Find a Grave

- ^ David M. Gitlitz & Linda Kay Davidson ‘’Pilgrimage and the Jews’’ (Westport: CT: Praeger, 2006), 118-120.

- ^ chabad.org

- ^ "Education and Sharing Day, U.S.A., 2003" by George W. Bush.

- ^ youtube

- ^ "Public Law 103-457". Thomas.loc.gov. http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d103:HR04497:%7CTOM:/bss/d103query.html. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ^ nmajh.org

- ^ a b c d e f g The Messiah of Brooklyn: Understanding Lubavitch Hasidim Past and Present, M. Avrum Ehrlich, Chapter 20, KTAV Publishing, ISBN 0881258369

- ^ 29/04/1991

- ^ Another 'Second Coming'? The Jewish Community at Odds Over a New Form of Lubavitch Messianism, George Wilkes (2002). Reviews in Religion & Theology 9 (4), 285–289.

- ^ a b Messianic Excess, David Berger, The Jewish Week, June 25, 2004

- ^ The Rebbe's Army: Inside the World of Chabad-Lubavitch by Sue Fishkoff, p. 274.

- ^ "THE LATEST NEWS | The Jewish Week (BETA)". The Jewish Week. http://www.thejewishweek.com/news/newscontent.php3?artid=7839. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ^ See section "Before Schneerson's Death".

- ^ See: "After Schneerson's Death".

- ^ Tomer Persico, Chabad's Lost Messiah, Azure, Autumn 2009.

- ^ "Lawsuit Over Chabad Building Puts Rebbe’s Living Legacy on Trial, The Forward, Nathaniel Popper, Mar 16, 2007". Forward.com. http://www.forward.com/articles/lawsuit-over-chabad-building-puts-rebbe-s-living/. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ^ Matthew Hirshberg (2006-02-21). "After Rebbe’s Death, Lubavitchers Continue to Spread His Word". The Columbia Journalist. ColumbiaJournalist.org. http://www.columbiajournalist.org/rw1_dinges/2005/article.asp?subj=city&course=rw1_dinges&id=718. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ^ Peter Schäfer; Mark R. Cohen. Toward the Millennium: Messianic Expectations from the Bible to Waco. Books.google.com. http://books.google.com/books?id=AT8GF9EciLEC&pg=PP1&ots=VnolvMMSDI&dq=Toward+the+Millennium:+Messianic+Expectations+from+the+Bible+to+Waco&sig=XAGONjYhL4w-0nsCKlThlWNZww8#PPA400,M1. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ^ Sefer HaTanya, Iggeret Hakodesh chapter 28, page 290. Kehot Publication Society, 1940–2010 ISBN 978-0-8266-0235-0

- ^ The Messiah of Brooklyn: Understanding Lubavitch Hasidim Past and Present, M. Avrum Ehrlich, ch.18, note 14, KTAV Publishing, ISBN 0881258369

- ^ Chabad's critic from within Tom Segev, Haaretz, January 17, 2008

Works

Books

- Hayom Yom – An anthology of Chabad aphorisms and customs arranged according to the days of the year.

- Haggadah Im Likkutei Ta'amim U'minhagim – The Haggadah with a commentary written by Schneerson.

- Sefer HaToldot – Admor Moharash – Biography of the fourth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Shmuel Schneersohn.

Personal notes and writings

- Reshimot – 10 volume set of Schneerson's personal journal discovered after his passing. Includes notes for his public talks before 1950, letters to Jewish scholars, notes on the Tanya, and thoughts on a wide range of Jewish subjects.(2,190pp)

Talks and letters, transcribed by others and then edited by Schneerson

- Likkutei Sichot – 39 volume set of Schneerson's discourses on the weekly Torah portions, Jewish Holidays, and other issues. (16,867pp)

- Igrot Kodesh – 30 volume set of Schneerson's Hebrew and Yiddish letters.

- Hadran al HaRambam – Commentary on Maimonides' Mishneh Torah.

- Sefer HaSichot – 10 volume set of Schneerson's talks from 1987–1992. (4,136pp)

- Sefer HaMa'amarim Melukot – 4 volumes of edited chassidic discourses.

- Letters from the Rebbe – 5 volume set of Schneerson's English letters.

- Chidushim UBiurim B'Shas – 3 volumes of novellae on the Talmud.

Unedited compilations of Schneerson's talks and writings

- Sefer HaShlichut – 2 volume set of Schneerson's advice and guidelines to the shluchim he sent.

- Torat Menachem – 40 volume Hebrew set of unedited Maamarim and Sichos currently spanning 1950–1964 (Approximately 4 new volumes a year). Planned to encompass 1950–1981.

- Sichot Kodesh – 50 volume Yiddish set of unedited Sichos from 1950–1981.

- Torat Menachem Hitva'aduyot – 43 volume set of Sichot and Ma'amarim from 1982–1992. (Based on participants' recollections and notes, not proofread by Rabbi Schneerson.)

- Karati Ve'ein Oneh – Compilation of Sichos discussing the Halachic prohibition of surrendering land in the Land of Israel to non-Jews

- Sefer HaMa'amarim (unedited) Hasidic discourses – Approx. 24 vols. including 1951–1962, 1969–1977 with plans to complete the rest.

- Biurim LePeirush Rashi – 5 volume set summarizing talks on the commentary of Rashi to Torah.

- Heichal Menachem – Shaarei – 34 volumes of talks arranged by topic and holiday.

- Torat Menachem – Tiferet Levi Yitzchok – 3 volumes of elucidations drawn from his talks on cryptic notes of his father.

- Biurim LePirkei Avot – 2 volumes summarizing talks on the Mishnaic tractate of "Ethics of the Fathers".

- Yein Malchut – 2 volumes of talks on the Mishneh Torah.

- Kol Ba'ei Olam – Addresses and letters concerning the Noahide Campaign.

- Hilchot Beit Habechira LeHaRambam Im Chiddushim U'Beurim – Talks on the Laws of the Chosen House (the Holy Temple) of the Mishneh Torah.

- HaMelech BeMesibo – 2 volumes of discussions at the semi-public holiday meals.

- Torat Menachem – Menachem Tzion – 2 volumes of talks on mourning.

Collections and esoterica

- Heichal Menachem – 3 volumes.

- Mikdash Melech – 4 volumes.

- Nelcha B'Orchosov

- Mekadesh Yisrael – Talks and pictures from his officiating at weddings.

- Yemei Bereshit – Diary of the first year of his leadership, 1950–1951.

- Bine'ot Deshe – Diary of his visit and talks to Camp Gan Israel in upstate New York.

- Tzaddik LaMelech – 7 volumes of letters, handwritten notes, anecdotes, and other.

Esoterica continue to be released by individual families for family occasions such as weddings, known as Teshurot.

Further reading

- Elliot R. Wolfson. Open Secret: Postmessianic Messianism and the Mystical Revision of Menahem Mendel Schneerson. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-231-14630-2

- Samuel C. Heilman & Menachem M. Friedman. The Rebbe. The Life and Afterlife of Menachem Mendel Schneerson. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, . 2010. ISBN 978-0-691-13888-6

External links

Works available online

- Chabad.org – Literature

- Sichos Kodesh – The Rebbe's original unedited talks 1950 – 1981 (Yiddish)

- Sichos B'Laha"k – The Rebbe's unedited talks (Hebrew)

- Sichos in English

- Igros Kodesh (Hebrew)

- Toras Menachem (Hebrew)

- Hayom Yom (Hebrew)

- The Rebbe's 10-point Mitzvah campaign

- Audio recordings of the Rebbe's addresses (Yiddish)

- More audio recordings of the Rebbe's addresses (Yiddish)

- The official archive of all the Rebbe's weekday talks (Yiddish)

Works available on iTunes

Biography

Historical sites

- The Ohel, about Schneersons burial site

- Proclamation of Education and Sharing Day 2002 by President George W. Bush also honoring the 100th birthdate of Rabbi Schneerson

- Education and Sharing Day, U.S.A., 2007

- Numerous proclamations by President Reagan citing work of Rabbi Schneerson and promotion of the Seven Noahide Laws

- Congressional Gold Medal Recipient Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson

- Tributes to the Lubavitcher Rebbe by Menachem Begin, Bill Clinton, Newt Gingrich, Israel Meir Lau, John Lewis, Joseph Lieberman, Yitzhak Rabin, Aviezer Ravitzky, Jonathan Sacks, Lawrence Schiffman, Adin Steinsaltz, Margaret Thatcher, Elie Wiesel and Elliot Wolfson.

- Family Tree

- Commemorative remarks upon the occasion of the 10th Yahrzeit of the Lubavitcher Rebbe Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb of the Orthodox Union

- Timeline of Menachem Mendel Schneerson 1928–1938

- My Encounter with the Rebbe, an oral history project undertaken by Jewish Educational Media, JEM to record the history of Rabbi Schneerson

| Preceded by Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn |

Rebbe of Lubavitch 1951–1994 |

Succeeded by N/A |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||